Policing, Racism and the Problem of Escalation

Building an Antiracist Community

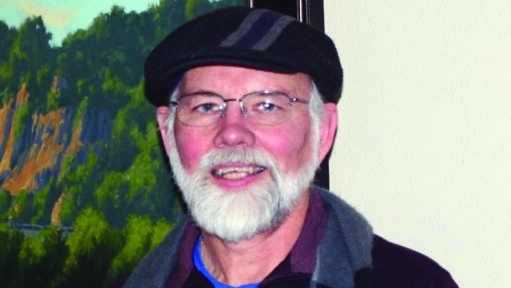

By Tim Johnson

I would like to say my wife and I never argue or get angry with each other. That, of course, would be neither honest nor believable. No one expects a couple that has been together for 38 years to have sailed through without a heated exchange or two. Fortunately, they have been rare, but one thing I have learned is that escalating a conflict never, ever leads to good results. Raising our voices, mutual accusations and all the other dimensions of escalation often only leads to greater distance and need for repair. What works better is going back to the basics, listening and treating one another the way we wish to be treated.

The failure of escalation in solving conflicts has also been my experience as a pastor working with my former congregation, engaging with the community, and with virtually any group with which I have been involved. Unless one is prepared to totally force the opposing party out of the picture, which sadly is sometimes the case, then finding ways to de-escalate, listen and show respect is the only viable option. This is no easy proposition, because when you are angry or fearful, showing dominance by escalating often feels like the natural thing to do.

The consequences of relying on escalation as a tool for confronting difficult situations are particularly problematic when it comes to policing. One wonders how it is that George Floyd, accused of the minor offense of using a counterfeit $20 bill, ended up dead at the hands of police. One wonders how Daunte Wright, a young 20-year-old African American, pulled over because of an invalid license tab and held because of a warrant for a minor offense, is killed by a 26-year police veteran who trains young recruits. Even if one accepts the assertion that this most recent incident was an “accidental” shooting, the question remains: Why did this officer feel it necessary to fire a life-threatening Taser at this young man? In the cases of both police officers, Derek Chauvin and Kimberly Potter, how did the situation escalate so quickly that a Black man lost his life?

Barry Brod, a use-of-force expert hired by Chauvin’s defense, makes it perfectly clear just how and why such situations unfold. According to the Star Tribune, “Brod told the court that Floyd’s death was not the result of deadly force. “Police officers don’t have to fight fair,” he said, adding that officers can escalate their use of force up a level from the force they are facing.” To put it simply, police are taught to escalate as a tool, a means of addressing difficult encounters. Escalation is the tactic of first resort in responding to African American men who themselves have an experiential reason to be afraid. Escalation is the tactic in responding to protestors angered at the killing of yet another black man. To be sure, there are police who take a different approach, but escalation is the governing norm.

None of this comes as a surprise for those who know something about the history of policing. According to Alex Vitale, author of The End of Policing, the origins of policing are tied to protecting the interests of the governing class by sustaining eighteenth century inequality, maintaining slavery and colonialism, and controlling the new industrial working class. He goes onto say, “basic functions of managing the poor, foreign and nonwhite on behalf of a system of economic and political inequality remains.” Vitale states U.S. models for policing were developed from British colonial occupation of Ireland and U.S. occupation of the Philippines, both grounded in a drive for domination. If domination is the goal, then escalation is a logical tool. When one adds racism to this mix, something that policing as an institution shares with the rest of our culture, it comes as little surprise that black men die with such tragic frequency at the hands of police.

Unless we are unambiguously committed to maintaining policing as a vehicle of control and domination, particularly for low-income people and communities of color, it is time to rethink our approach to law enforcement. Escalation in times of conflict is an utter failure when it comes to a marriage or partnership. Escalation in times of conflict only leads to greater division when used as a tool in a church, the community or any group that finds itself at odds. Why, then, do we continue to operate as if escalation will somehow prove effective for police? It is past time that we support our police officers with alternatives that begin with listening and treating those they encounter the way they wish to be treated, even in the most difficult situations.

Tim Johnson is a retired pastor of the United Church of Christ.