Mosquitoes, Guns and Racism

Building an Antiracist Community

Mosquitoes, Guns and Racism

As a young girl my daughter quickly grasped the concept that creating breeding spots for mosquitoes was a bad idea if you wished to avoid being assaulted by these troublesome creatures. When I showed her the mosquito larvae swimming about in a bucket we had unintentionally left outside, her response was an unequivocal, “dump it out”.

Somehow, this basic wisdom of a child escapes us when it comes to guns. Sadly, West 7th Street now finds itself on a national register of areas shocked and shaken by a mass shooting, with 14 injured and a young 27-year-old woman dead. A couple people with history and animosity decided to settle their dispute by shooting at each other inside the crowded Seventh Street Truck Park. As is commonly the case, there are those who argue that what is needed to prevent this type of assault is more guns. Increasing the number of guns when gun violence is already at an epidemic level makes as much sense as putting out more mosquito attracting buckets in the summer, ignoring how doing so contributes to the problem. More places for mosquitoes to breed mean more mosquitoes. More guns mean more gun violence. It’s not all that complicated.

The question is, what is it that keeps us from going beyond the rhetoric of dismay and assertions of “never again” to developing strategies and responses that address this national epidemic? It was only recently that the Federal government ended a 20-plus year ban prohibiting the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention from studying the causes and best way to prevent gun violence. Why such resistance? What is to be feared by a careful analysis of this national epidemic? It would seem if one wishes to avoid future Truck Stop shootings, then understanding the nature of gun violence is an excellent place to start.

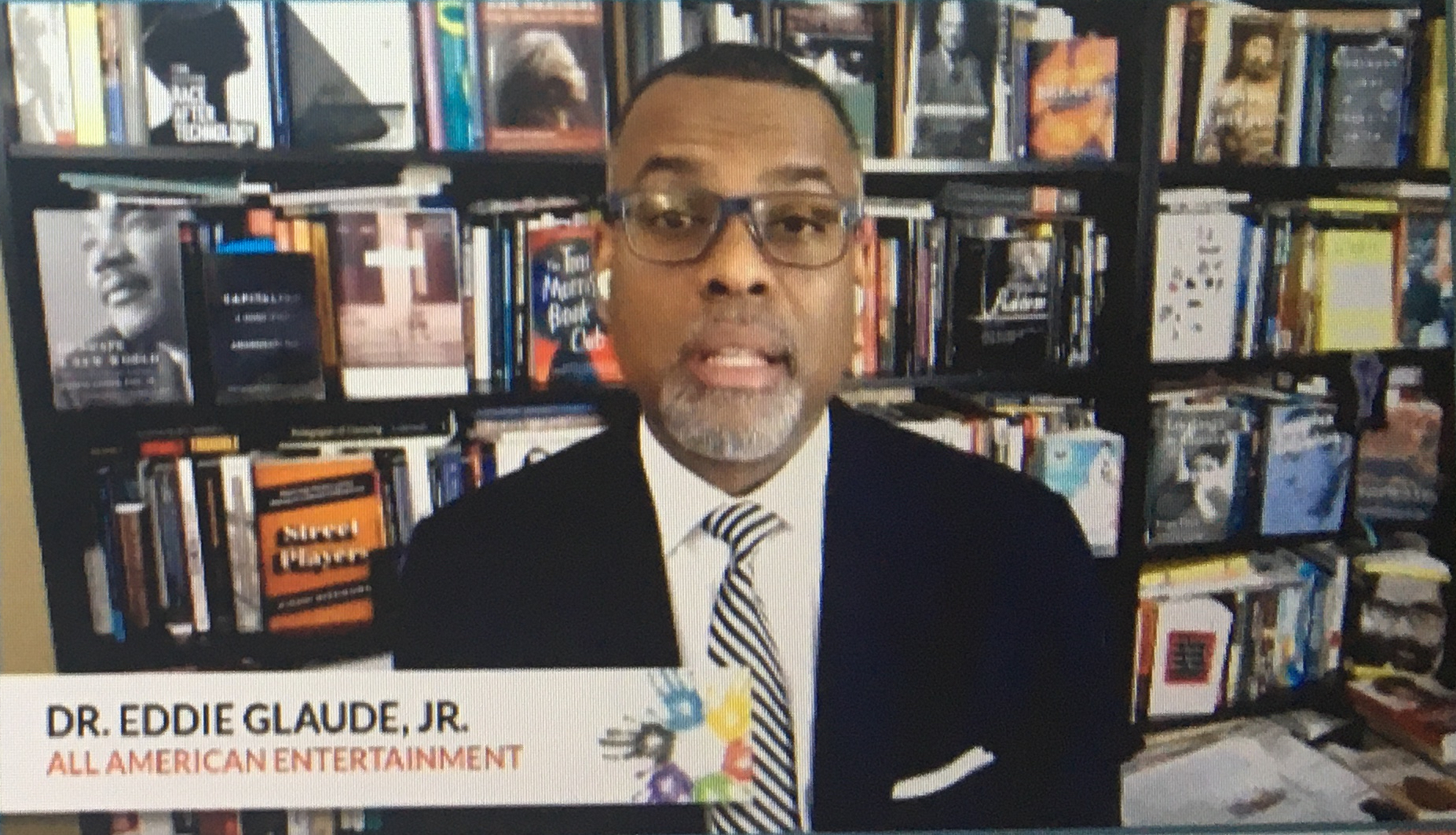

According to Dr. Jonathan Metzel, author of Dying of Whiteness, a great deal of the resistance to practice and policies preventing gun violence comes directly from a desire to protect and defend whiteness. By this Metzel does not mean white skin, but rather a deeply entrenched ideology that holds white skinned people superior to all others, especially to Blacks. Metzel, along with many other scholars, notes that the origins of the 2nd Amendment had much less to do with citizens protecting themselves from a tyrannical government. It had everything to do with upper-class whites encouraging, even requiring, lower-class whites to quell both slave rebellions and Indigenous resistance. Guns and racism were joined at the hip at our nation’s birth.

White racial fears about changing demographics and growing diversity are ripe for manipulation by those who aggressively seek to maintain a hierarchy that greatly rewards those with the highest incomes, while offering small change and superior status to low-income whites. It is both tragic and ironic that the white men most resistant to seriously addressing gun violence are, according to Metzel, the ones who suffer the most from gun violence. He notes, “A white person in the United States is five times as likely to die by suicide using a gun as to be shot with a gun.” The American narrative, including the Westerns with which many of us grew up, teaches us that white men are the defenders of the social order and that guns are central to that order. Yet the tragedy is that the inherent racism of guns in the defense of whiteness ends up causing the deaths of white men at an alarming and disproportionate rate. As Metzel notes, “white men themselves become the biggest threat to themselves.”

The anxiety now felt on West 7th Street among store owners, patrons and residents did not occur in a vacuum. It is a part of a long national history involving race and gun violence. Sadly, that violence manifested itself at the Seventh Street Truck Stop. To be sure, addressing gun violence can be a complex undertaking, but on another level, it can be as basic as “dump it out”.

Tim Johnson is a retired pastor of the United Church of Christ.