When the Gangsters Ruled St. Paul

by David Lamb

A century ago, the “Public Enemy Number One,” the leader of the group whose members J. Edgar Hoover called “the toughest mob we ever cracked,” roamed the streets of St. Paul. His name was Alvin Karpis, and for five years he orchestrated dozens of robberies out of his St. Paul base, protected by paid-off police and an instinct for smelling trouble and skipping town. In Alvin Karpis and the Barker Gang in Minnesota by Deborah Frethem and Cynthia Schreiner Smith, the St. Paul of the gangster era springs vividly to life again.

Born Albin Francis Karpowicz in 1908 in Montreal, Alvin “Creepy” Karpis, as he came to be known, was a precocious criminal who became a mastermind. At the age of 10, he helped a teenager rob a grocery store, breaking in late at night and “picking it over like vultures.” By age 17, he was in prison in Kansas, serving his first sentence for burglary. There he met his mentor, Larry DeVol, with whom he broke out of the prison in 1929. The two embarked on a crime and murder spree across Kansas and Colorado that was only brought to a halt a year later, when Kansas City police found a trove of safe-cracking tools in the trunk of their motorcycle.

In the resulting prison stint, Karpis’ second, he met Freddie Barker, already an experienced robber, who would become the other guiding force of the Karpis-Barker gang. With Barker’s “itchy trigger finger” and Karpis’ experience as “a strategist who liked planning jobs, figuring escape routes and running numbers,” they made a formidable team. After being paroled, they proved their chemistry through a streak of large robberies.

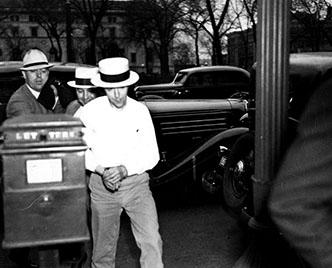

shortly afer the kidnapping of Hamm’s Brewery president,

William R. Hamm. (Photo courtesy of St. Paul Historical Society.)

Their move to Minnesota came as a result of a crime run amok. The day after robbing a store in Missouri, Karpis took his sputtering 1931 DeSoto to an auto mechanic. When it was recognized as one seen at the robbery, the sheriff was notified and then, arriving at the shop, killed. Karpis became wanted for the murder, and St. Paul, which teemed with corruption, was the only haven where he could find safety.

The Green Lantern, a long-ago demolished speakeasy on Wabasha Street in downtown St. Paul, was the naturalization site of sorts. There, Freddie Sawyer, the saloon’s owner and the man who brought Karpis to St. Paul, introduced him to a coterie of gangsters. Karpis wrote that the assembly, which included “escapees from every major US penitentiary,” left him “dazzled.”

With the Green Lantern as his unofficial “headquarters” and a home base in West St. Paul, Karpis’ gang terrorized the Midwest, robbing banks throughout Kansas, Wisconsin, North Dakota and South Dakota.

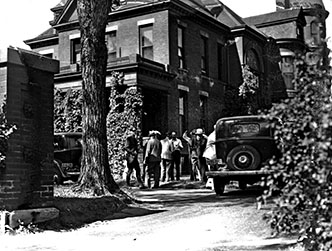

One day, a West St. Paul neighbor, realizing that Karpis was wanted for a killing of an officer in Kansas, reported a tip in person to Inspector James Crumley of the St. Paul police, and Karpis’ criminal career might have come to end. But it turned out that Crumely happened to be, as Frethem and Smith write, the “right-hand man to corrupt police chief Tom Brown,” and so he proceeded to lock the confused tipster in a file room while he phoned Chief Brown and stalled the inevitable police raid. In an image that captures the frequent attempts to apprehend Karpis and his associates, the police swarming his house found only his lukewarm, partially eaten breakfast.

Eventually, after the gang murdered two Minneapolis police officers as they escaped a robbery, Karpis decided to turn his attention to a more lucrative venture: kidnapping. For his first target, he snatched William R. Hamm, president of St. Paul’s Hamm Brewery. The abduction of one of the city’s most prominent businessmen — a story fed by the ransom notes Karpis left behind in a booth at a pharmacy on Grand Avenue — riveted the city.

Astonishingly, Karpis remained under the radar for several more years. With Brown feeding false clues to federal authorities, the FBI wasn’t even aware of Karpis’ gang, instead pinning the Hamm kidnapping on a rival gangster. Details like that one, expertly unfurled in this sordid biography, make certain parallels to the present unavoidable. Tragic failures at the highest levels — from the current White House’s bungling of a coherent COVID-19 response to the inability of the FBI and CIA to circumvent the terrorism attacks of 9/11 — have never proven entirely avoidable. And contrary to the elaborate conspiracies some invent to explain them, the real reasons behind these failures are often as simple and mundane as the payroll on which Karpis kept many of St. Paul’s police.

His gang went on to kidnap Ed Bremer, president of the Commercial State Bank and the son of the president of the Schmidt Brewery. By then, J. Edgar Hoover had grown suspicious of Brown; and Karpis, who had since been discovered by the FBI and swiftly named as its number one most-wanted fugitive, was within Hoover’s sights, the “last major criminal of the gangster era still on the loose.”

The manhunt would not proceed smoothly for Hoover. He was hauled before a Senate appropriations committee, grilled over his failures and criticized for shooting up houses without successfully capturing Karpis. Yet Hoover was not someone to ever let criticism stop him.

Filled with dozens of photos of the men — and one woman — in Karpis’ gang as well as of the places across St. Paul that their dangerous lives took them, Frethem and Smith’s book is a captivating glimpse into a shadowy era in the city’s history that, for better and for worse, shaped the place we inherit.