158 Years Post-Emancipation, St. Paul Turns to Reparations

by David Lamb

“This is where I used to live,” Linda Garrett sometimes tells her grandchildren as they zip down I-94 through St. Paul. But instead of gesturing at one of the fenced-in homes along Concordia Avenue or toward any number of other streets that overlook the highway, she points down at the roadway itself. In the late 1950s and the ’60s, the City of St. Paul gradually acquired the Rondo neighborhood via eminent domain, eventually bulldozing the place where more than 80 percent of Black St. Paulites once lived to make way for the interstate. After growing up in a home on Rondo Avenue, purchased by her great-grandmother in 1907, Garrett was one of the children forced to move.

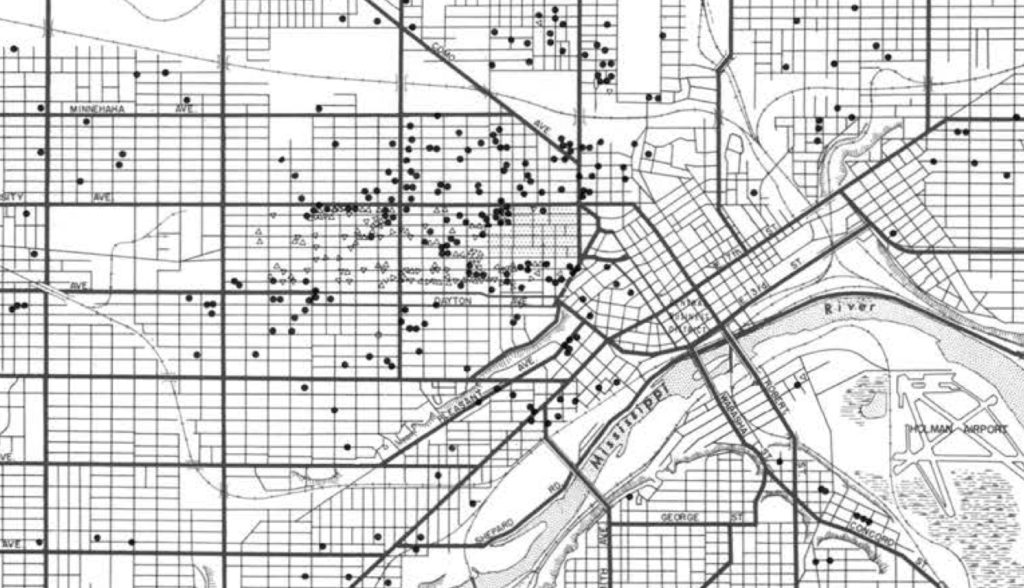

Criticism of the decision to dismantle the city’s Black cultural, business and religious hub has only grown in strength in the decades since. Marvin Anderson, a former Rondo resident who collaborates with a onetime neighbor to run the annual Rondo Days festival, told the Star Tribune last year that he believed city planners selected the area for the I-94 project because they could buy the land inexpensively and without political pushback. Others have condemned the effects the decision had on displaced families. After being forced from their homes in the neighborhood, many struggled to purchase houses elsewhere in the region because of racial covenants that at the time often prevented Black people from buying properties.

The destruction of Rondo, those covenants keeping many Black residents out of the neighborhoods left intact and other forms of structural racism in St. Paul are all topics of the resolution that the city’s councilmembers passed unanimously on January 13. It calls for the formation of a new commission to study reparations for the descendants of American slavery now living in St. Paul.

The resolution points out that after slavery was abolished in the U.S., former slaveholders were reimbursed for what the government considered a loss of property, while formerly enslaved people were given no compensation for their lifetimes of exploitation and abuse. It also draws attention to Minnesota’s involvement in slavery—though it was illegal in the territory, some were kept in bondage at Fort Snelling, including Dred and Harriet Scott, the plaintiffs in the landmark Supreme Court case that ruled Black people were not conferred Constitutional rights, later overturned by the by the Fourteenth Amendment.

CITY OF ‘SUBTLE RACISM’

Garrett, now 70, remembers a form of what she calls “subtle racism” prevalent throughout institutions of the city in previous decades. Her father, James Stafford Griffin, who worked for the St. Paul police department for 42 years, experienced it repeatedly: first after passing his civil service test to start working on the force, only to be told he had failed the physical exam on account of his flat feet; later as he finally succeeded at the dubious physical evaluation to became one of four Black officers in the city; and toward the end of his career, when he sought a promotion to the role of deputy chief of police. Despite attaining the top exam score among candidates for the second-in-command position, which had previously been awarded based on the test, Garrett’s father didn’t get the nod, she said. Instead, he discovered that the chief had already made up his mind to promote another candidate, going so far as to print new stationery. Only when her father hired a lawyer and threatened a discrimination lawsuit was he allowed to share the job with the colleague whose score he bested.

“That is one kind of discrimination that’s happened a lot,” Garrett told the Community Reporter. “In hiring, with the trade unions, which controlled whether you could become a carpenter or a plumber, and with housing.”

Growing up in Rondo, where businesses—often themselves Black-owned—catered to Black customers, Garrett described feeling insulated from some of the racism that she came to better understand in adulthood. But she also remembers taking swimming lessons at a public pool in Highland Park as a child in the ’60s and being confused by other kids telling her and her siblings to “get out of our pool.” And how, on a family road trip to California, her father brought with him a letter from his supervisor, signed on the man’s letterhead, assuring that he was a police officer of good moral character. One evening in Nevada, as they looked for a place to stay, motel after motel with vacancy signs hanging outside turned the family away. Garrett watched from the car’s backseat as her father drove to a small-town police station, handed the sheriff his letter and begged him to call a hotel to tell them he had a family at the station that he wanted a room for.

“Until white America can start understanding the humiliation, the hurt, the roadblocks that were placed that explain many of the issues that we have today,” Garrett said, “we won’t get anywhere.”

‘POWER IN APOLOGY’: TAKING ON INEQUITY

St. Paul’s city councilmembers hope the reparations commission will provide an important step to understanding those experiences and changing the conditions that facilitated them. “Part of this is about accountability,” said Councilmember Rebecca Noecker, who represents Ward 2. “Local governments like ours were not innocent in perpetuating Jim Crow and systems of exclusion. We need to apologize, and there is a power in apology.” Yet Noecker said the resolution is far from empty words. “With the commission, we are looking backward to take responsibility but also looking at the present to see how our racial divisions are hampering us and looking to the future to determine what we can do to address these inequities.”

The resolution puts St. Paul at the forefront of a national movement. Last year, Asheville, North Carolina and Evanston, Illinois became the first American cities to approve programs seeking to make reparations for slavery.

The two local activists who brought the initiative to the City Council, Trahern Crews and independent journalist Georgia Fort, were not fazed by the fact that no U.S. municipality of St. Paul’s size had attempted such a program. For months, they coordinated meetings with individual councilmembers to rally their support.

The idea of enacting reparations on the local level came to Crews in 2018 after he had spent three years studying the racial wealth gap. He realized that the hurdles that stopped other attempts at reparations could be overcome in the right contexts and began developing the concept for the new resolution, which is officially called the St. Paul Recovery Act. “When we first started the process,” Crews wrote in an email, “I didn’t know it was going to be unanimous.”

Even though a city budget may not allow for the largest-scale solutions, Noecker felt that she and her peers needed to pursue reparations because, unlike in Congress where scant legislation has passed in recent years, cities and counties are closer to the problems Americans face and more able to take action. “In city government,” she said, “we’re on the ground level. So we can see these big systemic challenges that are hurting people in a way that others might not. We can see how the fraying of the social safety net has affected our residents during the pandemic, how racial divisions factor in.”

In the public comments on the resolution, some residents disapproved. “Apparently the council is unaware that this great nation fought a civil war to end the immoral subjugation of slave[ry],” wrote Betty Newburgh, who lives in St. Paul. “Our First Minnesota is still regarded with awe,” she noted later in the letter, “because of our suicidal charge at Confederate troops at Gettysburg that allowed precious minutes for the Union to regroup.” Several other residents registered support for the reparations commission.

Rev. Curtiss DeYoung, CEO of the Minnesota Council of Churches and coauthor of Radical Reconciliation: Beyond Political Pietism and Christian Quietism, is one of several religious leaders to endorse the initiative. He pointed out that the Twin Cities have sharp racial disparities—“some of the most extreme in the U.S.,” he told this newspaper—a reality that led his organization to launch the Truth and Reparations Project last October, a 10-year-long racial justice initiative. “I hope we can work in partnership with the City,” DeYoung said, adding that the two initiatives can “learn from each other.”

Rev. Grant Abbott, the former executive director of the organization now called Interfaith Action of Greater St. Paul, who worked for years to bring together diverse religious groups to fight for progressive causes, described the resolution as vital. “There’s a logic behind why we need to take action now,” he said. “We know that the inequity in income and generational wealth is growing, largely because of the structure of the economy, with those who are able to invest getting richer and richer.” For Abbott, understanding the need for reparations begins with accepting how, aware of it or not, regardless of whether their particular ancestors enslaved anyone, white people have in his words “been riding on the wave of inequity for more than 150 years….As the great Rabbi Abraham Joshua Heschel said, ‘We’re not all guilty, but we’re all responsible.’”

If only we could go back in time. Loved their parades their music and their love of life. So sad this was taken away from them. I am an East Sider and I also laws raised in the happy times.