The City of St. Paul was birthed with the expulsion of immigrants by the U.S. military. In the 1600s French explorers, traders and missionaries came to the Midwest via Canada and the Great Lakes. In 1811 the Red River Colony or Selkirk Settlement was founded on 116,000 square miles of land that included parts of Manitoba, Saskatchewan, Ontario, Minnesota and North Dakota. Many settlers had Native (Ojibwe) wives and their descendants made up a unique métis population and culture. The language was primarily French, with Native and English added.

Life on the prairie was brutal: ferocious winters, locusts and mosquitoes, disease, floods and prairie fires, conflicts with native tribes and lack of experience in developing the prairie for agriculture. After an 1826 flood colonists walked their cattle to Fort Snelling, a six-month 700-mile journey. Between 1821 and 1835 it is estimated that close to 500 refugees from Selkirk’s Colony found refuge at Fort Snelling.

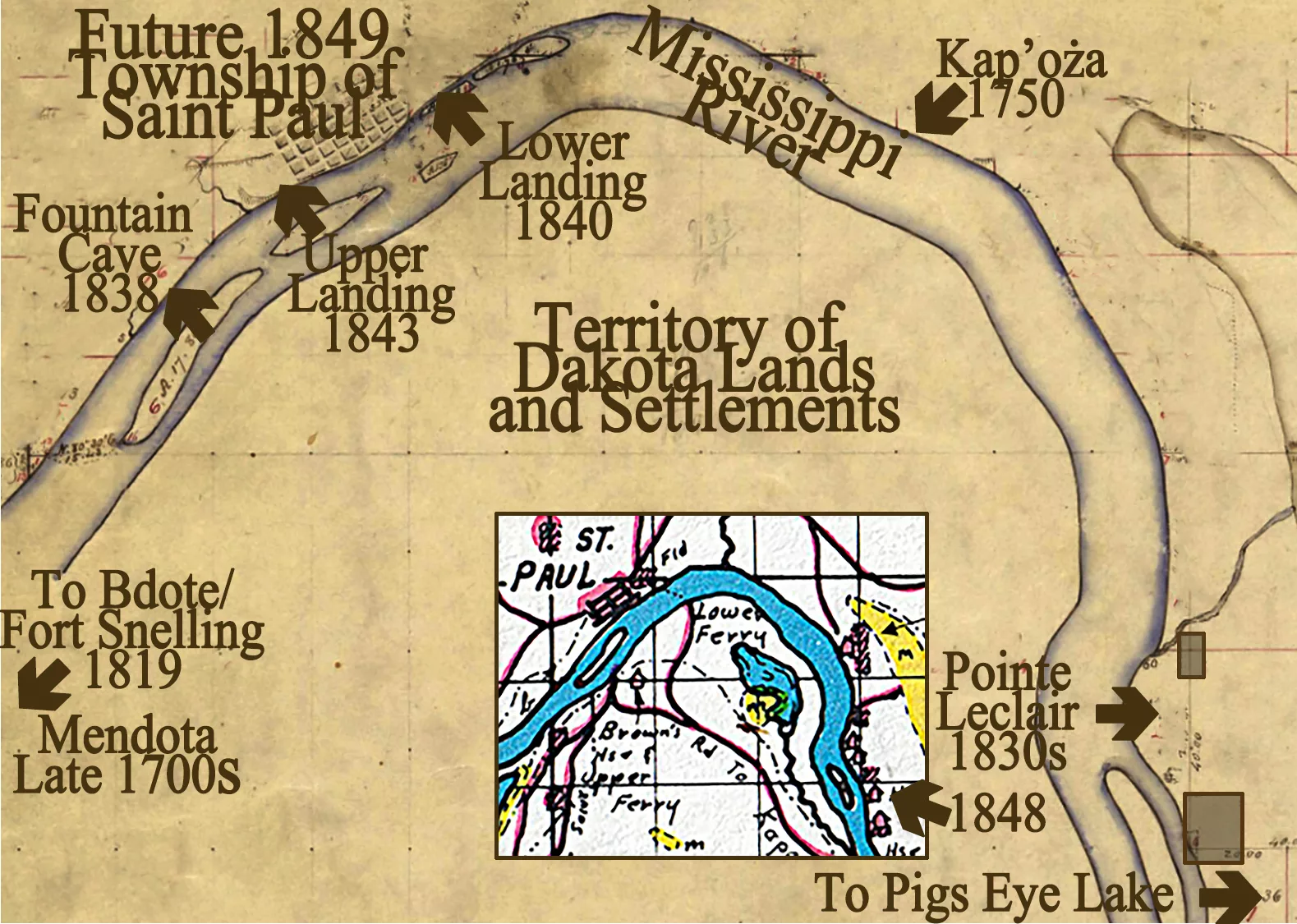

The 1837 Land Cession Treaty with the Dakota opened territory east of the Mississippi River for American settlement. The Dakota Kap’oża/Kaposia village was moving to the river’s west bank near South St. Paul, originally located below Mounds Park. In 1838 Major Joseph Plympton redefined the boundaries of Fort Snelling’s military reserve and forced civilian settlers out with their first stop at Fountain Cave. In 1841 he again expanded the fort’s boundary and literally burned out that community. The refugees relocated with their livestock to make claims in what is now St. Paul’s downtown plateau above its bluffs as well as at Pointe Leclair/Point Basse two miles south.

About 1830, French Canadian Michel Leclaire was probably first to settle the future St. Paul. His claim was at the Grand Marais along the Mississippi River that became known as Pointe Leclaire/Le Clere’s, two miles south from Wakan Tipi/Carvers Cave. Michel was a carpenter and employed others at the point in building houses and logging. He built a house for Alexander Faribault in 1835/1836, and windows and doors for Vital Guerin’s first house about 1840. The Leclaire family included Apisti, his Dakota wife and six boys and five girls. Their first, Antoine, was born in 1825 in Gilman, Minnesota, about 80 miles north of St. Paul; the last was Marie, born in 1847 a year before Michel died. The children’s baptisms were in Mendota at St. Peter’s Catholic Church by Father Galtier and Bishop Loras. Census records of 1839 and 1850 have the family at Pigs Eye/Red Rock that became a St. Paul dump 1956-85 and is currently a Superfund site.

In 1839 the fluid community at Pointe Leclair included nine cabins and the families of Antoine LeClaire (Michel’s brother), Francis Gammel, Raphael Lassarte, Joseph Labisonnière, Henry Belland, (Basil Labbe dit) Chevalier, Charles Mousseau and Amable Turpin (1766-1866). Voyageurs worked for the American Fur Company in Mendota across from Fort Snelling part of the year and farmed with their families at Pointe Leclair the rest. Documentation for these settlers comes from Bishop Loras’ marriages, baptisms and confirmations in Mendota in 1839 and 1840 in an early primitive chapel.

Michel Leclaire died in1849 (buried in Calgary Cemetery) before he was able to purchase his homestead claim from the federal government, north of Pigs Eye Lake. When Apisti died in 1852, the children became orphans. William Forbes, a fur trader and territorial legislator, stepped in and secured the homestead. Guardianship of four of the children was awarded to Edmund Brissett in 1855. Following Michel’s death the French-speaking communities eventually merged at the Lower Landing to become a major northern commercial stop for steamships, and eventually the railroads of JJ Hill—and our future City of St. Paul.

How Pigs Eye gets credit

In 1839 after a six-month stay at Fountain Cave, Pigs Eye Parrant relocated to Michel Leclair’s settlement and lived with Edmund Brissett “…helping to build houses and get out logs”. All did not go well. Historian J Fletcher Williams placed Pigs Eye on Bench Street at the Lower Landing for about a year after the Fall of 1839. However both Lucien Galtier and Bishop Mathias Loras reported that only Edward Phelan’s log house was at the landing in 1840. The area was swamp and marsh and subject to flooding.

Parrant made a claim at Pointe Leclair, and counter claims between Parrant and Leclaire came before Justice of the Peace Joseph R. Brown’s court in Dacotah, county seat of St. Croix County. In 1844 a jury trial decided for Leclair; Parrant lost. Williams further confused history with a myth of a foot race between Parrant and Leclair to decide the claims! Parrant then relocated to the St. Croix River with a woman and five-year-old child and returned briefly to sell liquor at the Lower Landing before disappearing altogether. Thus Parrant’s role as founder of St. Paul is suspect.

Long story short, while Pigs Eye’s colorful moniker gave a lake near Pointe Leclair its name, it was eight exiled settlers and Father Lucien Galtier that built an embryonic chapel that branded St. Paul.

To be continued…

Based on the A History of the City of Saint Paul, and of the County of Ramsey, Minnesota (Williams, 1876); The Letters of Letitia Hargrave (MacLeod 1947); Tells of Early Days in St. Paul (McNulty, The Saint Paul Globe, December 09, 1902); New Light on Old St. Peter’s and Early St. Paul (Hoffmann, Minnesota History , March 1927); Correcting Mystery and Myth Not Everything You’ve Heard about Pig’s Eye Parrant is True (Goff, Ramsey County History, 2021); The Tales and Times of Isaac Labissionière (Labine 2025) Origin Story (Landsberger 2025).

Leave a Reply